An Article in the

Metropolitan

Remembering the Negro Leagues at 92

by Eric Eames

The Metropolitan

The atmosphere oscillates in Room 3F at the Denver Educational Senior Citizens apartment building.

It´s magical

It´s historical.

Jacquelyn Benton, Byron Johnson´s daughter, opens the door dressed in a striped uniform with the Kansas City Monarch´s crown symbol patched on the front. A glass case reflects sparkles and nostalgia into your eyes from prized baseball regalia and pictures.

The Masters is on, of course. Johnson is keeping a devoted tab on Tiger Woods. Later, he´ll flip to the Colorado Rockies game and that´s when the phone goes unanswered, because baseball isn´t just a past time.

Baseball is his time.

From 1937-to-1938, Byron "Mex" Johnson played in the Negro Leagues for the famed Kansas City Monarchs. As black baseball´s glamour franchise, the Monarchs sent the most players to the Major Leagues once the racial wall crumbled when Jackie Robinson made his debut for the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947.

Also, in 1939 and 1940, Johnson traveled the nation and played on Satchel Paige´s All-Star team, which frequently barnstormed against white "all-star" teams put together by Dizzy Dean or Bob Feller. Surviving records of these contests and other exhibition games, dug up by baseball historian John Holway, show the black stars winning 269 of the 438 contests played between 1887 and 1947.

Johnson recalls beating Feller´s squads by scores of 11-1 and 14-2. While Feller chose players from both the American and National leagues from the Majors, Satchel Paige´s All-Stars were just an extension of the Kansas City Monarchs, says Johnson. So they had team spirit and team unity, and that´s better than a bunch of separate individuals patch-worked together.

"We weren´t only as good as them, we were better," Johnson says. "They finally had to recognize that. It wasn´t that we weren´t good enough, they just never gave us a chance. That is the way we had to play—under those conditions. I had some good days and some bad days, because (white fans) would always come and watch us play, but we couldn´t go to their restaurants to eat a good meal. But that was the way we had to play if we wanted to play at all."

"We weren´t only as good as them, we were better," Johnson says. "They finally had to recognize that. It wasn´t that we weren´t good enough, they just never gave us a chance. That is the way we had to play—under those conditions. I had some good days and some bad days, because (white fans) would always come and watch us play, but we couldn´t go to their restaurants to eat a good meal. But that was the way we had to play if we wanted to play at all."

When Robinson, formerly of the Monarchs, bashed the color line, he brought the Negro Leagues´ electrifying style of sheer speed and base running to the grandest stage. Millions of Americans flocked to see Robinson. He was named Rookie-of-the-Year. He helped the Dodgers win six pennants in his 10 seasons. He stole home 19 times. He was named National League MVP in 1949. What more proof is needed to show that the Negro Leagues housed some of the greatest players of all time?

"He was better than a lot of the players," Johnson said. "He made Rookie of the Year. He beat out all of them. What does that say to you now? Somebody has been lying about our ability."

What Johnson may fail to mention is that Robinson replaced him at shortstop when he left baseball to fight in World War II. And Johnson´s biggest regret was not getting a chance to play in the big leagues, because of his skin color. He could have taken care of his family and children better if he had.

Johnson has one reason, it may not be right, but he believes Kenesaw Mountain Landis, baseball´s first commissioner, knew what he was doing by barring black baseball players.

"We took lots of white boys out of their jobs," Johnson said, "because as soon as Jackie made it a lot of other teams added black players to their list."

In addition to Leroy "Satchel" Paige, Johnson played with Norman "Turkey" Stearnes, Wilbur "Bullet" Rogan, James "Cool Papa" Bell and Hilton Smith, who Johnson believes was a better pitcher than Paige. All five of the men are enshrined in the Major League Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown.

He also played against Theodore "Double Duty" Radcliffe and Josh Gibson. All legends.

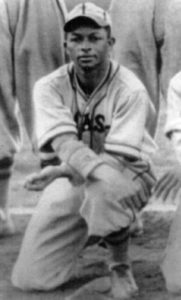

During his short stint, Johnson played to generally effusive reviews himself. He was hailed as the best shortstop in the league and perhaps the best shortstop in any league. He was The Wizard (Ozzie Smith) of his day, a nimble infielder with cat-like feet, unmatchable range to both sides and a bullwhip arm that would snap the ball to first to complete a textbook 4-6-3 double play.

Born in Little Rock, Ark., on Sept. 19, 1911, Johnson didn´t have a baseball rolled to him when he was an infant. It went against American etiquette in sport at the time to sell a white ball with red stitches to a black person. When Johnson was old enough to stroll the neighborhood to the vacant baseball diamonds, which were as frequent as basketball hoops are today, he carried a "Broom-hound" bat, apparently with the broom amputated, while a baseball took on several forms as did the base pads, which could have been a tin can, a rock, an old shoe or hubcap.

Born in Little Rock, Ark., on Sept. 19, 1911, Johnson didn´t have a baseball rolled to him when he was an infant. It went against American etiquette in sport at the time to sell a white ball with red stitches to a black person. When Johnson was old enough to stroll the neighborhood to the vacant baseball diamonds, which were as frequent as basketball hoops are today, he carried a "Broom-hound" bat, apparently with the broom amputated, while a baseball took on several forms as did the base pads, which could have been a tin can, a rock, an old shoe or hubcap.

"My first ball is the same Coca-Cola bottle cap you see today," Johnson said. "People ask me when did I start to play baseball. I tell them, I don´t ever remember not playing baseball."

He´d play the day away, bringing home to his mother Elizabeth, who died when he was 9-years-old, and his father Joe blisters, scuffed clothing and swollen hands from playing catch without a mitt. He also tugged around a pet goat in a homemade, all-wood wagon with nervous wheels, while wearing a large sombrero on his head, which created the nickname Mex.

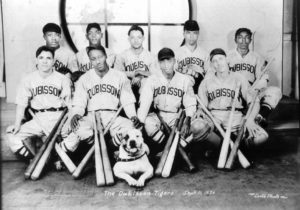

Johnson played semi-pro ball in 1932 for the Little Rock Stars. But it was in Shreveport, La., where the Monarchs spotted him playing and kept track of him when he headed to Wiley College in Texas on a football scholarship, where he caught footballs with one hand. At Wiley, Johnson earned a teaching degree and immediately got a job teaching at his high school alma mater—Dunbar High in Little Rock. Just when he was getting settled that´s when the Monarchs came calling and wanted him to tryout.

"I had heard of the Monarchs," Johnson said. "I knew they were one of the greats in baseball. But they were really over what I figured to have ever made. It´s just like a youngster now thinking they could make the Rockies. It was a privilege for me to try out for the Monarchs and I was so thankful that I did as well as I did."

On his first day in a Kansas City uniform in 1937 and after a long bus ride, Johnson met the man who already played shortstop for the Monarchs. Willard Brown was a power hitter, averaging two homers a game. Johnson didn´t think he had a chance to replace him. But the Monarch´s white owner, J.L. Wilkinson, still wanted to take a look at Johnson´s abilities and asked him to tryout during the middle of a game. Player-manager Andy Cooper obliged by inserting Johnson into the lineup, where the Cool-Whip smooth shortstop gobbled a hard grounder and instantly started a double play with a quick flip to the second baseman.

It was easy to him, but the crowd lapped it up. By the time he got back to the dugout, he had the job stolen from Brown who moved to the outfield. It was evidence of the athleticism Johnson has displayed since he was a toddler.

"What I didn´t know and the owner told me later, was that they had been looking for a shortstop for over a year that could make the double play," Johnson said. "And that´s how I made Kansas City Monarch baseball team."

There are other prisms through which the "Jim Crow" era of baseball and of the United States can be refracted. But the real players—players like Johnson—know better than to swallow the Hollywood version. No amount of stirring music can change it into a completely positive experience.

As a child, Johnson had to swim in the creek. It was water not fenced off and water no one cared about. The whites swam in a clean public pool.

Johnson watched movies with a squint from row dead last, and that was if they let him through the theatre doors. The whites sat up front, on the lower level; going back and forth with butter popcorn silos, cool sodas and American dreams.

Johnson had to stand next to the COLOREDS ONLY sign waiting for the spigot´s dry heaves to moisten, gurgle and spit. While the WHITES ONLY fountain freely flowed.

"It was hard to understand why they hated us," Johnson said. "I had never done anything to them. I never got into a fight with no white person. They tried to pick a fight with me. I just think these people hated me before I was born. I didn´t have a chance before I was born."

While playing for the Monarchs and Satchel Paige´s All-Stars, white fans would come and watch the black players play, especially in the 1930s when the stock market collapsed. With The Great Depression gripping the nation, people could barely afford to eat, so they were not spending money to see ball games.

But with Paige working his magic on the mound—using antics like telling his defenders to sit on their gloves for an inning—and with the invention of night baseball, the Monarchs still drew an adequate number of fans and in some sense kept the game alive.

"Baseball was dying in America in the ‘30´s and who brought it back more than anyone man, I would have to say it was Satchel Paige," Johnson said. "Bob Feller didn´t draw any crowd like Satchel Paige."

But Feller was never shooed away by white hotel and restaurant owners.

In the Army during World War II, race lines were no different from that in the states. Out of all the things he remembers from the war—from landing at the site of D-Day just days after the initial assault on Normandy and 18 days of combat—what Johnson remembers most is watching German prisoners enter a make-shift cafeteria through the front door, while he still had to go through the back way.

"That was one of the roughest times in my life," Johnson said. "I´m going to fight for my country and I have to go through the backdoor, but then my enemy is walking in the front door….

"I don´t try to sugar coat nothing. I´ll talk about the good, and the bad. I have some great white friends…. But I don´t like to dwell on it, because it´s making me angry now and I get all upset. I have white kids ask me questions. They say ‘Byron how is it that you don´t hate anybody?´ I say, ‘Well, I guess it was the training of my parents, what they taught me is what I believe.´ I don´t hate anybody."

It was baseball that winched Johnson through the segregation period. Playing the game was like pulling a blanket over his head. After it was over, the veil was removed to show things were still the same. But for those nine innings, Johnson didn´t see color or worry about where he was going to sleep that night. All he saw was a baseball and he had to get it and hit it and rip it across the diamond to the first baseman.

In 1938, Johnson gained recognition for his defensive talent and base running ability when fans voted him to the East-West Game (the equivalent to the Major League All-Star game) at Comiskey Park in Chicago. Before he left to represent the West, Stearnes let Johnson borrow his bat for the game and challenged Johnson. The deal was if Johnson got a hit, he could keep the bat. If he didn´t, then Stearnes wanted it back. Many years later, Johnson walked into the Negro League Baseball Museum in Kansas City, Mo., to donate the bat.

This February, John "Buck" O´Neal, who was also the Monarch´s player-manager and was in town to speak at Coors Field about Negro League baseball, stopped to visit Johnson. And when those two get together to reminisce they don´t bother counting words before spending them. Benton, who is an instructor for African American studies at Metro and whom Johnson has passed down all this history, sat down and admired more historical grandeur.

"I can remember Satchel Paige from when I was a little girl, meeting him when he came to play in Little Rock," Benton recalled. "My father took me out to a game with Satchel Paige. I knew he played with Satchel Paige, but that was before we moved here (to Colorado)…. I´ve known Buck O´Neal practically all my life too. I still call him Uncle O´Neal, because that is how I always referred to him.

"When I was a teenager and older, I knew about that history. I guess I didn´t really start thinking about it a lot myself until a lot of attention started coming to my father, which of course wasn´t until he was in his 80s, which of course has been about 10 years ago.

"And I think it wasn´t probably until then that I did really recognize the fact that this is history. He´s history. Of course, I´m fortunate, because I´m with him, so I get to hear the stories all the time about when he played in the Negro Leagues, about all those great players he played with and played against. When Buck O´Neal comes in it is just wonderful to be in the room and hear them talking. I´ve had a chance to met Double Duty Radcliffe too and I got to hear him talk about his memories of my father. He called him a couple of things from what I can remember. He called him ‘The Man With The Arm.´ He also called him ‘The Vacuum Cleaner,´ because he said he snatched up every ball that tried to get passed him on the field."

Benton now takes care of her 92-year-old father. She rarely allows reporters to visit her father as often as before. Since December, Johnson´s motion has been reduced to a painful walker-aided shuffle. A nasty winter fall broke part of his hip, which has kept him from visiting Dr. Tom Altherr´s American Baseball History class at Metro for the first time in seven years.

He now sits gingerly watching the Rockies, shifting from time-to-time to relieve the pressure on his hip. A Budweiser can sits on the eating tray that strides his walker, along with peeled orange slices. His hands shake a little as he places his hearing aids. An ever-present baseball cap casts shadows on the light-brown polka-a-dot freckles on his cheeks and a smile for the ages.

His small, gnomic stature (5-feet 8-inches, no more than 120 pounds) belies the aura that surrounds him and the magnitude of the era he lived through, an era forgotten in many circles, an era where he says the best and most entertaining baseball was played.

And if history ever unravels all the statistics, a feeble prospect considering the lack of coverage from the white newspapers and defunct black publications, the proof will be hard to deny.